Over the course of two hundred years, the United States and Mexico have developed rich diplomatic, economic, and cultural ties but at times clashed over borders, migration, trade, and an escalating drug war.

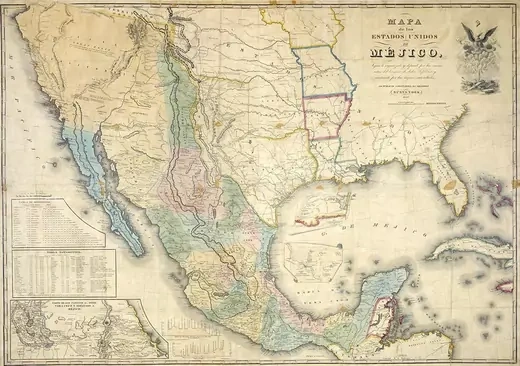

In 1810, Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla calls for Mexico’s independence from Spain, spurring a series of revolts across the country that becomes known as the Hidalgo rebellion. The rebellion fails, but fighting continues. Meanwhile, the United States and Spain are locked in a debate over the border between their territories. In 1819, the Adams-Onis Treaty, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, draws a definitive border between Spanish land and the Louisiana Territory. The United States cedes California, New Mexico, Texas, and territory that will become the states of Arizona, Nevada, and Utah to Spain; it also agrees to pay U.S. citizens’ land claims against Spain up to $5 million. In 1821, Mexico gains independence from Spain under the Treaty of Córdoba.

1810 – 1821 1835 – 1836Migration is the root of the first dispute between the United States and Mexico. In 1830, Mexico prohibits immigration to Texas from the United States in an effort to stem the influx of English-speaking settlers. Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna tries to enforce the law by abolishing slavery and enforcing customs duties. In March 1836, Santa Anna is taken prisoner and signs a treaty recognizing the independence of Texas.

1835 – 1836 1845 – 1846

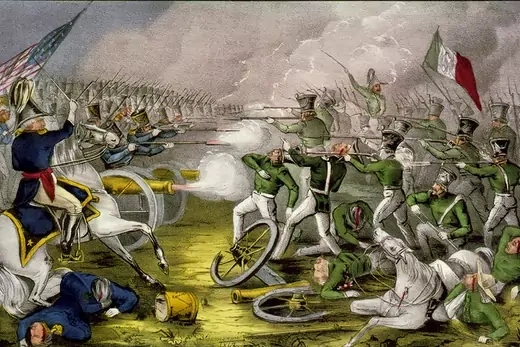

In 1845, Texas becomes a U.S. state where slavery is legal. Shortly after, Mexico breaks off diplomatic relations with the United States. Meanwhile, U.S. President James K. Polk offers to purchase California and New Mexico from the Mexican government and seeks to make the Rio Grande River the border between the two countries, which would make Texas part of the United States. Advocates of “Manifest Destiny,” the nineteenth-century concept that the United States had a moral obligation to expand to the Pacific coast, support the plan. Mexico refuses Polk’s offer, and Polk sends military forces to the Rio Grande in retaliation. Fighting ensues, followed by a full-scale U.S. invasion, during which an estimated 1,700 thousand people are killed.

1845 – 1846

After the seizure of Mexico City, the United States and Mexico ratify the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ending the Mexican-American War. The treaty obligates Mexico to cede territory that will become Arizona, California, and New Mexico, as well as parts of Colorado and Nevada. In return, the United States pays $15 million in compensation for war-related damage to Mexican land. The treaty also provides for the protection of the property and civil rights of the roughly eighty thousand Mexican nationals living in U.S. territory. Many become U.S. citizens, but most lose their land by force or fraud. The California Gold Rush prompts gold seekers to push out Mexican landowners.

U.S. President Franklin Pierce purchases thirty thousand square miles of land along the Mesilla Valley, which runs from California to El Paso, Texas, for $10 million. He plans to use the land for a transcontinental railroad to the Pacific Ocean. The Gadsden Purchase, as it becomes known, also resolves an outstanding border dispute between Mexico and the United States, and marks the last adjustment to the border between the two countries.

1882 – 1910

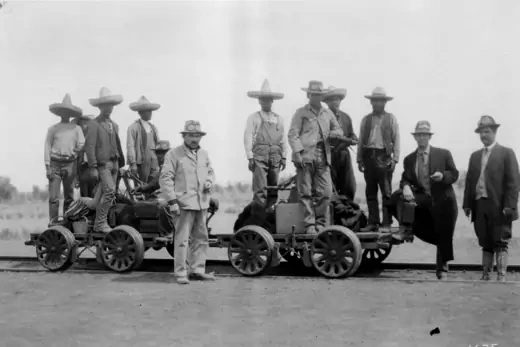

Labor shortages in the United States lead railway companies to recruit Mexicans after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 halts immigration from China. Meanwhile, inspection stations are set up at ports of entry along the southern border. In 1904, the first U.S. border patrol is established to stop Asian workers from circumventing border controls and entering through Mexico. Historians estimate that more than sixteen thousand Mexicans were working on the railroads by the early 1900s, representing as much as 60 percent of the U.S. railway labor force at the time.

1882 – 1910

Unrest among Mexican peasants and urban workers triggers the Mexican Revolution, with rebel forces led by Emiliano Zapata Salazar in the south and Francisco “Pancho” Villa in the north. In 1911, dictator Porfirio Díaz, who famously said, “Poor Mexico, so far from God and so close to the United States,” is overthrown, and Francisco Madero assumes the presidency. The bloody conflict and political upheaval causes a flood of Mexican immigrants to seek refuge in the United States. Between 1910 and 1920, more than 890,000 Mexicans migrate to the United States, although some of them ultimately return.

April 1914A year after President Madero is killed in a coup led by General Victoriano Huerta, nine U.S. soldiers are arrested and detained by Huerta’s army for allegedly entering a prohibited zone in Tampico, Mexico. The Mexican government apologizes, but U.S. President Woodrow Wilson sends marines to occupy the port of Veracruz to “obtain from General Huerta and his adherents the fullest recognition of the rights and dignity of the United States.” The invasion, which leads to the deaths of nineteen Americans and hundreds of Mexicans, inflames anti-American sentiment in Mexico, and Huerta flees the capital soon after due to ongoing political upheaval.

Villa, who attained notoriety as a general during the Mexican Revolution, leads hundreds of Mexicans in an attack on the U.S. town of Columbus, New Mexico, in retribution for U.S. support of his political rivals. The assault, the first military incursion on U.S. territory since 1812, kills at least sixteen Americans and destroys much of the town center. U.S. President Wilson responds to public outrage by sending ten thousand troops into Mexico in pursuit of Villa. They withdraw a year later, having failed to apprehend the guerrilla leader.

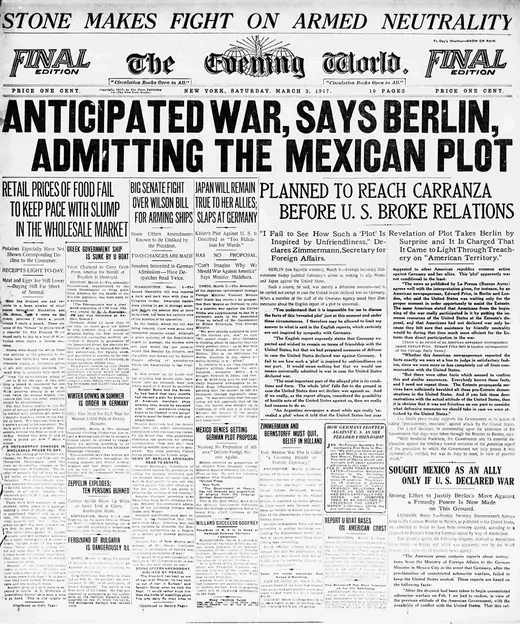

March 1917

With the United States remaining neutral as World War I rages in Europe, Germany’s foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann, sends a secret telegram to his Mexican counterpart, offering to restore territories Mexico lost in the Mexican-American War in exchange for an attack on the United States. Mexico dismisses the proposal, but the telegram is intercepted and published, leading to public outcry and a U.S. declaration of war against Germany in April 1917. Soon after, the United States recognizes the government of General Venustiano Carranza, leader of one of the factions of Mexico’s civil war, in exchange for Mexico’s continued neutrality.

1921 – 1929

The U.S. Congress passes the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, which restricts the flow of Southern and Eastern Europeans into the country; Mexicans are excluded from quota requirements. The subsequent Immigration Act of 1924 extends the restrictions to East and South Asians. The act establishes border stations to formally admit Mexican workers and to collect visa fees and taxes from those entering. That same year, the U.S. Border Patrol is created. By 1930, the U.S. census counts six hundred thousand Mexican immigrants residing in the United States, but Mexicans still comprise less than 5 percent of the immigrant workforce, not including undocumented immigrants who cross the border informally.

1921 – 1929 1929 – 1939

Economic collapse pushes tens of thousands of farmers in the U.S. Midwest to migrate to California in search of work, and Americans begin to view Mexican workers as competitors for jobs and a drain on social services. This prompts federal authorities to begin a repatriation program for Mexicans and Mexican-Americans, including some U.S. citizens, that forcibly relocates more than four hundred thousand people from Arizona, California, and Texas to Mexico. Wary of the political climate, hundreds of thousands more return to Mexico voluntarily.

1929 – 1939 1938 – 1944

Rising economic nationalism in the wake of the Mexican Revolution causes U.S. oil companies to fear their investments in Mexico could be expropriated. The 1923 Bucareli Treaty, in which Mexico agreed to respect the rights of oil companies in exchange for U.S. recognition of the sitting Mexican government, sought to settle the issue, but in 1938, Mexican President Lazaro Cardenas reverses that position and nationalizes the oil industry. The United States accepts the move to keep Mexico aligned with the Allied powers during World War II, though it presses for compensation; in 1944, Mexico agrees to pay U.S. oil companies $24 million plus interest.

1938 – 1944

Harry S. Truman becomes the first U.S. president to visit Mexico City. Later that year, the United States, Mexico, and twenty other Western Hemisphere countries sign the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance, or the Rio Treaty. It codifies the “hemispheric defense doctrine,” the principle that an attack against one country will be considered an attack against all countries. The Rio Treaty is invoked several times during the Cold War, including during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, and the United States cites it following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. In 2002, Mexico becomes the first country to formally withdraw from the treaty, which it does in protest over U.S. plans to invade Iraq.

The end of the Bracero temporary worker program [PDF] in 1964 prompts hundreds of thousands of migrant workers to return to Mexico. In response to the resulting demand for jobs, in 1965, the Mexican government establishes an industrial development program [PDF] focused on the U.S.-Mexico border. So-called maquiladoras, or “assembly plants,” are built to employ lower-paid Mexican laborers who will assemble goods for the U.S. market using raw materials sourced from the United States. Maquiladoras quickly become magnets for job seekers living further south; by 1992, the plants employ roughly half a million people and export goods worth $19 billion, or about 40 percent of Mexico’s total exports. The “Mexican Miracle” [PDF], the result of this state-directed economic plan, produces sustained annual economic growth of 3–4 percent for nearly three decades.

In September 1969, U.S. President Richard Nixon declares a global war on drugs, and the United States deploys thousands of agents along the U.S.-Mexico border to execute an aggressive search-and-seizure counternarcotics operation. The action disrupts cross-border trade, and Mexico’s displeasure over not being consulted on the operation leads to a bilateral cooperation agreement between the countries. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), created in 1973, becomes the primary point of counternarcotics cooperation. However, the 1985 assassination of a DEA agent in Mexico and growing frustration over Mexican authorities’ involvement in the drug trade lead Washington to favor an increasingly unilateral counternarcotics strategy.

1986 – 1994Despite the 1976 discovery of massive oil reserves in the Gulf of Mexico, the 1980s see the Mexican economy struggle with rising inflation, widespread unemployment, and unsustainable public debt [PDF]. Mexico defaults in 1982, sparking a regional debt crisis and leading Washington to step in to negotiate debt reduction in exchange for economic reforms. Many economists blame Mexico’s protectionist policies for its economic stagnation, and in 1986, the country takes the first steps toward reducing its trade barriers by joining the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the precursor to the World Trade Organization (WTO). Two years later, Carlos Salinas de Gortari is elected president on a reform platform. Salinas pushes to further deregulate the economy, paving the way for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

1986 – 1994 January 1, 1994

NAFTA goes into effect, beginning the fifteen-year process of eliminating tariffs between the U.S., Canadian, and Mexican economies. The deal creates the world’s second-largest trading bloc, after the European Union, and opens the door to expanded diplomatic cooperation between the United States and Mexico on issues including military training, environmental degradation at the border, central bank cooperation, and rule of law. The agreement proves controversial: U.S. labor groups and many Mexican farmers oppose it, and some critics later blame [PDF] the trade liberalization measures for U.S. job losses and increased illegal migration from Mexico. Still, most economists conclude that the deal boosted overall economic growth, including by more than tripling North American trade, and helped transform Mexico’s economy.

December 1994

Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de León, of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), is elected president and immediately faces a banking crisis when the value of the Mexican peso plunges in international markets. After U.S. President Bill Clinton fails to get congressional approval for the Mexican Stabilization Act, which would have provided Mexico a $50 billion bailout, fears that a Mexican default could shake the U.S. economy help him obtain a $20 billion loan from the Treasury Department to help Mexico stabilize its currency. Mexico reenters the international capital market by January 1997, but its economic woes continue after low oil prices and the 1997 Asian financial crisis lead to lower-than-expected growth.

President Clinton becomes the first U.S. leader to visit Mexico since 1979. He promises Mexican President Zedillo that he will avoid mass deportations of undocumented immigrants and commits to a joint strategy for combating drug trafficking. The plan centers on stopping the flow of drugs into the United States, including by tracking illegal firearms, negotiating new extradition agreements, and allowing DEA agents to be armed while on Mexican soil. Critics worry that the increased cooperation will compromise Mexican sovereignty. By the late 1990s, the United States represents less than 5 percent of the world’s population but consumes roughly half of all drugs globally.

After seven decades of uninterrupted power, the PRI is ousted when Vicente Fox, a member of the opposition National Action Party (PAN), is elected president. Fox takes office vowing to expand trade relations with the United States, reduce corruption and drug trafficking, and boost wages and economic growth. Meanwhile, U.S. President George W. Bush takes office in January 2001 and calls Mexico the most important U.S. foreign policy priority. However, U.S. attention wanes after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and subsequent war on terrorism define U.S. foreign policy for the next two decades.

Presidential candidate Felipe Calderón, a member of the conservative, pro-business PAN party, wins the July election by less than one percentage point over left-wing populist candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador, also known as AMLO. A limited recount confirms the result, but López Obrador claims fraud and mobilizes his supporters to stage mass protests, leading to a protracted legitimacy crisis that threatens to extend beyond Calderón’s chaotic December inauguration. Calderón’s support for expanded trade, immigration reform, and economic liberalization offers Washington a chance to bolster relations on multiple fronts. President Bush, under pressure from his own party, signs legislation in October to authorize seven hundred miles of new border fencing, which the Mexican government opposes.

2007 – 2009

The U.S. government says Mexican drug traffickers pose the biggest organized crime threat to the United States and backs an escalation of the drug war launched by Calderón. The Mexican president deploys thousands of federal troops throughout the country to fight cartels and other organized crime groups and establishes a new federal police force. In 2008, the United States and Mexico begin implementing the Mérida Initiative, a counternarcotics cooperation framework that provides Mexico roughly $400 million a year in assistance, including military aircraft, surveillance software, and airport inspection equipment. Meanwhile, drug-related killings soar; in 2009 alone, more than 9,600 people are killed in connection with organized crime.

2007 – 2009 March 2010

U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visits Mexico City to discuss border security and counternarcotics efforts after the killings of three people linked to the U.S. consulate in the city of Ciudad Juárez. They are the latest victims of a dramatic increase in drug trafficking–related violence in the wake of Calderón’s war against the cartels. Over the course of his six-year presidential term, there are more than 120,000 registered homicides [PDF], at least half of which are estimated to involve organized crime. U.S. and Mexican authorities introduce a “new stage” in bilateral border cooperation named ‘Merida 2.0’ [PDF], which expands aid to Mexico to fight drug trafficking and reorients the initiative’s focus toward improving social and economic conditions.

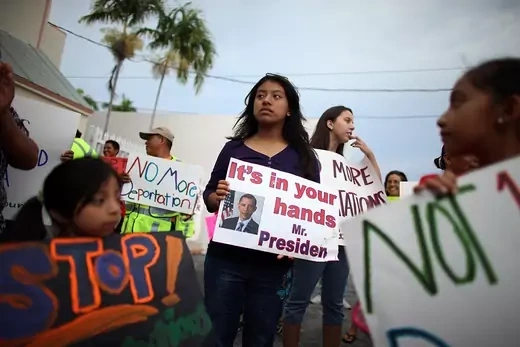

During a meeting in Mexico, U.S. President Barack Obama and Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto announce further bilateral cooperation on countering drug trafficking and organized crime. They also reveal the creation of a High-Level Economic Dialogue meant to deepen trade ties, which totaled half a trillion dollars in the previous year. Obama later calls on the U.S. Congress to pass a comprehensive reform bill to address the United States’ “broken immigration system.” The bill aims to improve border security, streamline the visa process, and provide a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, including nearly twelve million Mexicans. Peña Nieto expresses his support for the bill, though it ultimately fails in Congress.

The election of U.S. President Donald Trump threatens to upend the U.S.-Mexico relationship after he campaigns on promises of deporting huge numbers of undocumented immigrants, making Mexico pay for a new wall along the border, and ending NAFTA. Over the next four years, his administration implements several hardline immigration policies, including the “Remain in Mexico” program that sends asylum seekers back to Mexico, and a COVID-19 pandemic–related public health measure that closes the border to all migrants. Amid a 2019 surge in arrivals of migrants from Central America, Trump also threatens to impose tariffs on Mexico unless the government curbs migration through its territory. Mexico threatens retaliatory tariffs, but ultimately a trade war is averted, and Peña Nieto deploys the military to enforce the country’s immigration laws.

December 1, 2018

AMLO wins the presidency on his third attempt, representing the National Regeneration Movement, or Morena, a broad left-wing coalition. He promises to improve public security and reduce violence, tackle corruption, and address inequality. He also seeks to reverse many of Pena Nieto’s reforms to the energy sector—which allowed for expanded foreign investment—in the name of “energy sovereignty.” AMLO vocally opposes Trump’s efforts to build a border wall and his zero-tolerance border policy, but the two leaders nonetheless forge close economic and political ties over the next few years, including a shared desire to reduce the flow of migrants from Central America. In 2019, Mexico surpasses Canada and China to become the United States’ top trading partner, with bilateral trade totaling $615 billion [PDF].

July 1, 2020The U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), an updated version of NAFTA, enters into force nearly three years after negotiations began. Although Trump had called NAFTA “the worst trade deal in history,” the new agreement retains most of the original provisions, with several significant changes. These include tighter auto manufacturing rules that require more car production to originate in North America; reformed dispute resolution mechanisms; and stronger labor protections. While the labor provisions win bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress, some longtime critics maintain that the deal does not do enough to prevent U.S. job losses. Likewise, Mexican experts are concerned that Mexico’s auto, steel, and aluminum industries could struggle to meet new requirements. AMLO, however, hopes USMCA will help attract foreign investment. The deal is the main topic of discussion during his July 8 visit to the White House.

October 2020

DEA officers in Los Angeles arrest former Mexican defense minister Salvador Cienfuegos on drug trafficking charges. In retaliation, the Mexican government threatens to restrict DEA operations. U.S. authorities drop the charges and allow Cienfuegos to return to Mexico, where the government declines to pursue the matter. The incident brings attention to the increasing political influence of Mexico’s drug trafficking groups and stokes nationalist sentiment against what some Mexican leaders see as heavy-handed U.S. intervention. In response, Mexico’s Congress passes a law promoted by AMLO that will strip foreign agents of diplomatic immunity and require that they share any intelligence obtained in Mexico with the Mexican government. Analysts say the measure threatens to sharply reduce drug-war cooperation.

U.S. President Joe Biden’s hopes of reorienting U.S.-Mexico relations quickly face numerous challenges. Biden suspends Remain in Mexico, but a court ruling forces him to restart the program. On the drug-war front, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken visits Mexico in October to discuss a new strategy to replace the Merida Initiative, which Mexican officials declare “dead” amid spiking cartel violence and record flows of drugs, especially fentanyl, across the border. Frustrated with AMLO’s increasing reliance on the Mexican military, U.S. officials hope to instead strengthen civilian police forces, invest in public health, and address illegal firearms trafficking. Biden reopens the southern U.S. border in November 2021, though pandemic-era restrictions on migrants remain in effect. The United States donates nearly eleven million vaccine doses to Mexico, the most to any Latin American country.